“Saha Guidelines” and Mental health

Context: The Supreme Court’s judgment in ‘Sukdeb Saha vs The State Of Andhra Pradesh’, acknowledges mental health to be an integral part of the right to life

Case: Sukdeb Saha vs State of Andhra Pradesh .

-

Death by suicide of a 17-year-old NEET aspirant in Visakhapatnam hostel.

-

Father’s plea for CBI probe was initially rejected by the High Court but accepted by the Supreme Court.

-

Outcome: CBI inquiry ordered + recognition of mental health as an integral part of Article 21 (Right to Life).

Key Constitutional Significance

-

Expands Article 21: Right to life includes psychological integrity and mental health.

-

Converts mental health from statutory right (Mental Healthcare Act, 2017) → fundamental right.

-

Establishes a normative benchmark for citizens to claim safeguards.

Structural Victimisation & Criminological Angle

-

Student suicides = structural victimisation caused by:

-

Neglect of mental health policies.

-

Exploitative coaching culture.

-

Institutional indifference.

-

-

Extends victimology lens: students as victims of systems and institutions, not just personal failures.

-

Links to Johan Galtung’s theory of structural violence → harm caused by systemic neglect = as blameworthy as direct violence.

The “Saha Guidelines” (Binding Interim Orders)

-

Applicable to schools, colleges, hostels, and coaching centres.

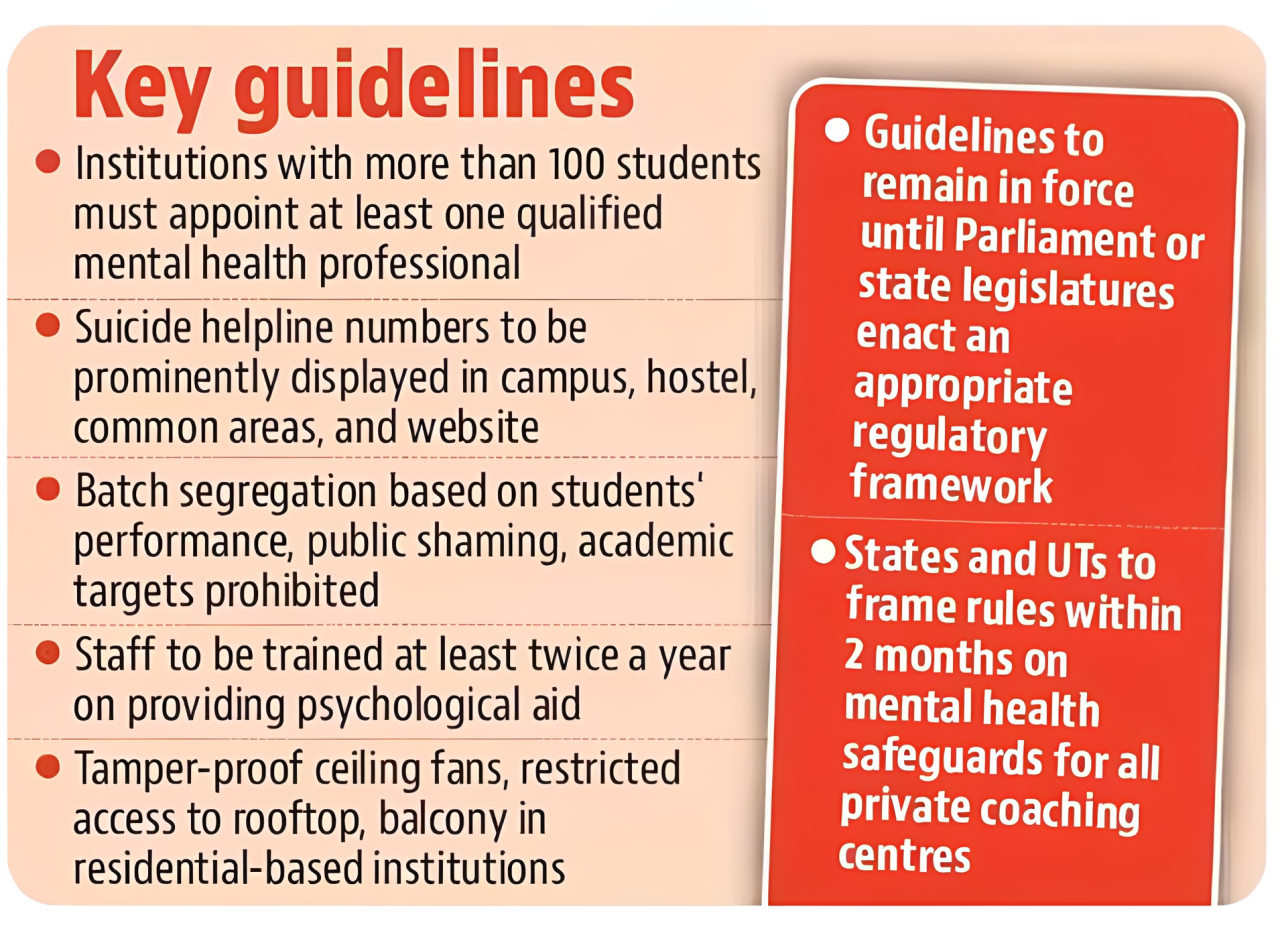

1. Institutional Policy Framework

-

Mandatory Mental Health Policy in all schools, colleges, coaching centres, and hostels.

-

Must align with national programmes: UMMEED, MANODARPAN, National Suicide Prevention Strategy.

2. Counsellor Requirement

-

At least one qualified mental health counsellor per institution with 100+ students.

-

Larger institutions must scale counsellor strength proportionately.

3. Safe Learning Environment

-

Prohibition of harmful practices:

-

Batch segregation based on academic performance.

-

Public shaming of students.

-

Imposition of unrealistic academic targets.

-

4. Access to Helplines

-

Helpline numbers (e.g., Tele-MANAS, local helplines) to be displayed prominently in campuses and hostels.

5. Staff Training

-

All staff (teachers, wardens, administrators) to undergo biannual mental health training.

-

Training includes crisis response, identification of warning signs, and first-line support.

6. Inclusivity & Non-Discrimination

-

Institutions must adopt inclusive practices.

-

Special protections for SC/ST/OBC/EWS, LGBTQ+ community, and persons with disabilities.

7. Confidential Redressal Mechanisms

-

Confidential reporting systems for sexual assault, ragging, and identity-based discrimination.

-

Institutions must ensure immediate psychosocial support for affected students.

8. Reducing Exam-Centric Stress

-

Shift away from exam-only focus.

-

Promote interest-based career counselling and encourage extracurricular activities.

-

Mandates:

-

Development of support systems for student mental health.

-

States/UTs to notify rules within 2 months.

-

Creation of district-level monitoring committees.

-

-

Until Parliament enacts a code, these guidelines have legislative force.

Challenges Ahead

-

Implementation bottlenecks: Will schools, universities, and states invest in mental health care?

-

Cultural stigma around mental illness still persists.

-

Risk of judgment being reduced to symbolic without resource commitment.

Implications

-

Legal: Elevates mental health as part of fundamental rights jurisprudence.

-

Criminological: Expands accountability of state and institutions as structural perpetrators.

-

Social: Demands recognition of students’ mental well-being as central to governance and education reforms.

Conclusion

-

The Sukdeb Saha verdict is a landmark blending law, criminology, and victimology.

-

It confronts an uncomfortable truth: neglect and structural pressures can be as deadly as direct violence.

-

Success of this judgment depends on institutional compliance, budgetary support, and cultural change.

-

By affirming that “the right to life includes a healthy mind”, the Court has amplified the voice of a silenced generation.

Article 21 landmark judgments

| Case Name | Year | Principle / Key Ruling under Article 21 |

|---|---|---|

| A.K. Gopalan v. State of Madras | 1951 | Narrow view: Article 21 protection is only against executive action. Legislature could deprive by enacting law. |

| Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India | 1978 | Expanded scope of Article 21: Right to life = dignified existence; personal liberty is of widest amplitude; freedom of speech has no geographical barriers. |

| Sunil Batra v. Delhi Administration | 1978 | Recognised prisoners’ right to dignity; prisoners are not mere chattels of the State. |

| Hussainara Khatoon v. State of Bihar | 1979 | Free legal aid and speedy trial are fundamental rights of the accused under Article 21. |

| Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation | 1985 | Right to livelihood is integral to right to life; eviction without just and fair procedure violates Article 21. |

| NALSA v. Union of India (Transgender Rights Case) | 2014 | Recognised transgender persons’ rights; entitled to all fundamental rights including life and personal liberty. |

| Puttaswamy v. Union of India | 2017 | Declared Right to Privacy as a fundamental right under Article 21. |

| Common Cause v. Union of India | 2018 | Recognised Right to die with dignity (passive euthanasia) as part of Article 21. |

| Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India | 2018 | Decriminalised homosexuality; affirmed privacy, dignity, and sexual orientation as protected under Articles 14, 15, 19, and 21. |

| Sukdeb Saha v. State of Andhra Pradesh | 2025 | Court held mental health is a fundamental right under Article 21. Introduced Saha Guidelines: binding interim measures for schools, colleges, hostels, and coaching institutes to provide support systems, States/UTs to notify rules within two months, and district-level monitoring committees. Elevated psychological well-being to constitutional protection. |