National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance (NAP-AMR 2.0) (2025-29)

Context: Why AMR is a One Health challenge

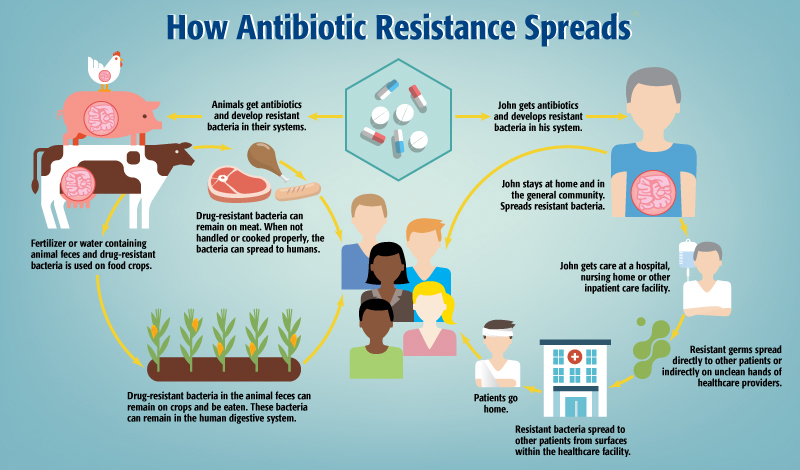

AMR now affects human health, veterinary practices, aquaculture, agriculture, waste systems and the entire food chain.

Antibiotic residues, resistant organisms and environmental discharge spread through soil, water, livestock, markets and food systems.

AMR does not remain confined to hospitals; it moves across ecological and food networks, making it a true One Health issue.

Hence, national-level plans require coordinated governance across sectors and levels of government.

Evolution from the first National Action Plan (2017)

Achievements of the first plan

Brought AMR into national policy consciousness.

Encouraged multi-sectoral participation.

Improved laboratory networks and expanded national surveillance.

Strengthened antimicrobial stewardship.

Embedded AMR within a One Health framework linking human, animal and environmental health.

Weaknesses in implementation

State-level execution remained limited.

Only seven States formulated State Action Plans:

Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Delhi, Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Sikkim, Punjab.Most States continued fragmented, sector-wise initiatives without integrated One Health structures.

Core determinants of AMR lie under State jurisdiction:

Health administration

Hospital functioning

Pharmacy regulation

Veterinary oversight

Agricultural antibiotic practices

Food-chain monitoring

Waste governance

National guidance alone could not ensure uniform implementation when operational levers sit with States.

Lessons from past programmes

India’s successful public health programmes (National TB Elimination Programme, National Health Mission) show progress when Centre and States work in a structured, mutually accountable system with:

Joint reviews

Shared monitoring

Clear division of responsibilities

Dedicated funding mechanisms

What NAP-AMR 2.0 adds (2025-29)

Strategic and operational enhancements

More mature and implementation-oriented.

Clearer timelines, responsibilities and resource planning.

Private sector integration

Recognises that meaningful progress requires involvement of the private health care and private veterinary sectors, which serve a major share of users.

Stronger scientific foundation

Focus on innovation:

Rapid diagnostics

Point-of-care tools

Alternatives to antibiotics

Strengthened environmental monitoring

Deepening of One Health perspective

More attention to:

Food-system pathways

Waste management

Environmental contamination

Integrated surveillance across human, veterinary, agricultural and environmental sectors.

Governance reforms

Higher-level oversight through NITI Aayog via a Coordination and Monitoring Committee.

Emphasis on establishing State AMR Cells and State Action Plans aligned with the national framework.

Introduction of a national dashboard for monitoring progress.

AMR is reframed as a national development priority, not just a technical public health issue.

Where NAP-AMR 2.0 falls short

No mechanism to ensure States actually:

Create AMR Action Plans

Establish AMR Cells

Implement their plans

No formal Centre-State AMR platform.

No joint review mechanism.

No statutory requirement for States to notify/implement plans.

No financial incentives (such as NHM-linked conditional grants).

This is critical because AMR determinants lie almost entirely under State jurisdiction.

Without structured political engagement and shared accountability, even a strong national plan may remain a technical document.

Need for a coordinated Centre–State mechanism

A national–State AMR council chaired by the Union Health Minister and guided by NITI Aayog:

Regular reviews

Joint decision-making

Coordinated solutions across health, veterinary, agriculture, aquaculture, food systems and waste/environment sectors

Union Government should formally request States to prepare and notify State Action Plans with annual reviews.

High-level communication (through Chief Secretaries) can improve administrative attention.

Conditional grants under NHM can strengthen surveillance, stewardship, infection control and laboratory capacity.

Success depends entirely on strong and accountable collaboration between Centre and States.

Way forward

NAP-AMR 2.0 provides a sound scientific and strategic base.

However, without a coordinated Centre–State architecture and financial pathways, it risks remaining a paper plan.

With structured coordination, political commitment and cross-sector participation, it can become a defining moment in India’s AMR response.

Prelims Practice MCQs

Q. Which of the following best explains why the first National Action Plan on AMR had limited success at the State level?

A. Lack of public awareness programmes

B. Determinants of AMR largely fall under State jurisdiction

C. Weak research ecosystem at national level

D. Excessive dependence on foreign laboratory systems

Correct answer: B

Explanation: Key AMR determinants—health services, pharmacy regulation, veterinary oversight, agricultural antibiotic use and waste management—are State subjects. Hence, without Centre–State mechanisms, uniform implementation was not possible.

Q. The NAP-AMR 2.0 deepens the One Health approach primarily by:

A. Focusing only on hospital-based antibiotic stewardship

B. Integrating surveillance across human, veterinary, agricultural and environmental sectors

C. Mandating bans on antibiotic use in agriculture

D. Centralising all veterinary regulation under the Union Government

Correct answer: B

Explanation: A key advancement is strengthened One Health integration through cross-sector surveillance and attention to food systems, waste and environmental contamination.

Q. Under NAP-AMR 2.0, national-level intersectoral oversight has been entrusted to:

A. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare

B. NITI Aayog through a dedicated Coordination and Monitoring Committee

C. Indian Council of Medical Research

D. Food Safety and Standards Authority of India

Correct answer: B

Explanation: Governance reforms place oversight with NITI Aayog, signalling higher-level intersectoral coordination.