Municipal bonds and fiscal architecture of urban local bodies

1. Context and Background

Urban India contributes nearly two-thirds of national GDP, yet municipalities control less than 1% of the country’s tax revenue.

This mismatch between economic output and fiscal empowerment reflects a structural flaw in India’s municipal finance system.

Municipalities depend excessively on intergovernmental transfers, loans, and centrally-sponsored schemes, limiting their autonomy.

2. Why the Fiscal Architecture is Flawed

(a) Over-centralisation of Taxation Powers

After the introduction of Goods and Services Tax (GST) in 2017, cities lost nearly 19% of their own revenue sources.

Key local taxes such as octroi, entry tax, and surcharges were subsumed under GST.

Compensatory mechanisms for municipalities were promised but not effectively delivered.

Result: Municipalities became fiscally dependent on higher governments, undermining local democracy.

(b) Fiscal Asymmetry and Inversion of Responsibility

Municipalities are responsible for essential services — waste management, housing, climate resilience, digital infrastructure — but lack the fiscal means to deliver them.

This results in a “centralised power, decentralised responsibility” model — contrary to the spirit of the 74th Constitutional Amendment (1992), which envisioned municipalities as autonomous tiers of governance.

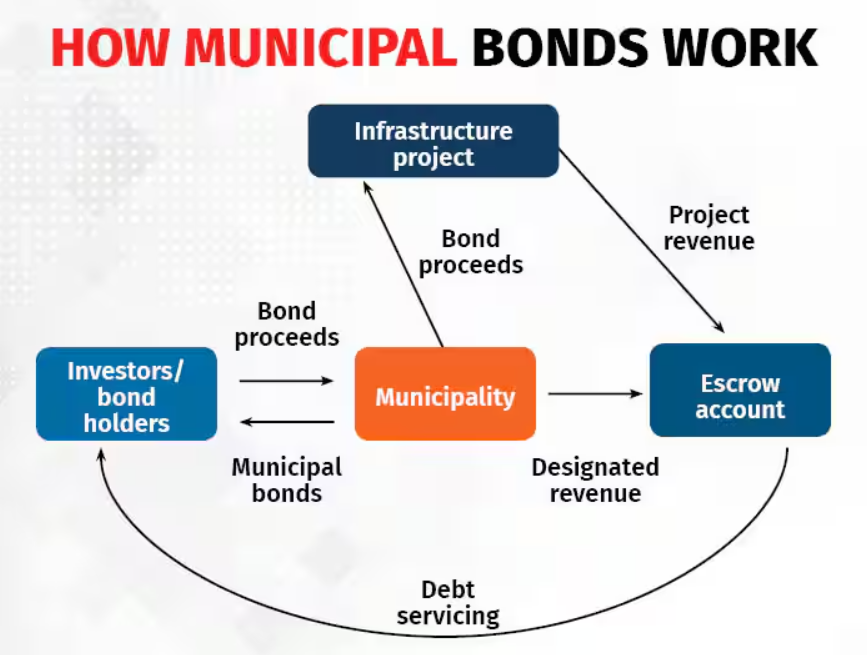

3. The Issue with Municipal Bonds

(a) Policy Push

Municipal bonds are being promoted by NITI Aayog and other policy bodies as the “new frontier of local finance.”

However, the credibility and uptake of municipal bonds in India remain abysmally low.

(b) Flawed Credibility Assessment

City creditworthiness is assessed only by “own revenue” performance — property taxes, user charges, etc.

Regular grants and transfers from State/Centre are discounted as “non-recurring income”, which is a conceptual and ideological error.

These transfers are constitutional entitlements, not charity.

(c) Inadequate Property Tax Dependence

Property tax contributes only 20–25% of municipal revenues and faces political resistance, poor assessment systems, and inefficient collection.

Excessive emphasis on property tax reform shifts the burden to residents, particularly low-income groups, violating principles of fiscal equity.

(d) “User Pays” Fallacy

The growing idea that “user pays” leads to efficiency is problematic.

Public goods like water, sanitation, mobility, and lighting are collective entitlements, not private commodities.

This trend converts public services into market products, undermining inclusion.

4. The Constitutional and Federal Perspective

The 74th Amendment intended to make cities equal tiers of governance, with access to a share of the national tax pool.

However, fiscal federalism remains highly asymmetric, with limited functional and financial devolution to local governments.

Grants are often scheme-based, tied, and conditional, restricting local innovation and responsiveness.

5. Lessons from Global Models

(a) Scandinavian Model (Denmark, Sweden, Norway)

Municipalities enjoy direct power to levy and collect income taxes.

Local taxes are the foundation of the welfare state.

Ensures transparency, accountability, and long-term planning at the local level.

Transfers from higher levels of government are viewed as part of a shared fiscal ecosystem, not as discretionary favours.

This model demonstrates that fiscal decentralisation can promote both efficiency and equity.

6. The Way Forward

(a) Reimagining Fiscal Federalism

Establish predictable, adequate, and untied revenues for municipalities.

Strengthen constitutional and formula-based transfers rather than discretionary grants.

(b) Reform Creditworthiness Framework

Recognise grants and shared taxes as legitimate city income in credit ratings.

Evaluate governance quality (audit compliance, transparency, citizen participation) — not just financial metrics.

(c) Municipal Bond Reform

Allow cities to use GST compensation or State share as collateral for bonds.

Develop risk-pooling mechanisms and State-level municipal development funds to improve creditworthiness.

(d) Strengthening Local Capacity

Build technical and administrative capacity for budgeting, financial management, and project execution.

Encourage citizen oversight and participatory budgeting to enhance accountability.

First Municipal Bond (1997):

Issuer: Bangalore Municipal Corporation.

Purpose: Infrastructure development.

Largest Issue (2018):

Issuer: Amaravati Capital Region Development Authority (CRDA).

Value: ₹2,000 crore.

Objective: Development of the new Andhra Pradesh capital region.

Municipal Bonds Key Features

-

Government-backed security: Lower default risk due to municipal ownership.

-

Tax benefits: Interest earned is often exempt from income tax, attracting retail and institutional investors.

-

Credit ratings:

-

Bonds are rated by agencies such as CRISIL, ICRA, and CARE.

-

Ratings improve transparency and investor confidence.

-

-

Tradability: Some municipal bonds are listed on stock exchanges, improving liquidity.

Recent Trends (FY18–FY26)

Between FY18 and Q2 FY26, 17 urban local bodies issued 23 municipal bonds, raising a total of ₹3,359 crore.

In the first half of FY26 (April–September 2025) alone, six municipalities have raised ₹575 crore.

An additional 7–10 ULBs are in the pipeline for bond issuance, indicating growing participation.

Projected FY26 total issuance: Around ₹2,000 crore, which is expected to be the highest annual issuance to date in India’s municipal bond market.

Challenges

Despite progress, the overall market size remains modest compared to international standards (e.g., U.S. municipal bond market > $4 trillion).

Limited investor base and low credit ratings of most ULBs.

Weak municipal accounting systems and delays in project execution.

Need for stronger revenue models (property tax, user charges, etc.) to assure timely repayment.