Metal-containing fine particles (MCFPs) on clear days

Usual way of judging air quality

Normally, governments and scientists measure PM2.5 (particulate matter smaller than 2.5 micrometres) to assess air pollution.

These particles can reach deep into the lungs and bloodstream, so high PM2.5 = poor air quality.

But a new study says this measurement alone can be misleading.

The study

Institution: East China Normal University

Published in: Environmental Health (2025)

Location: Shanghai

Method used: Single-particle inductively coupled plasma time-of-flight mass spectrometry (a technique to detect what each fine particle is made of).

Focus: Metal-containing fine particles (MCFPs) — small bits that include iron, aluminium, manganese, silicon, and lead.

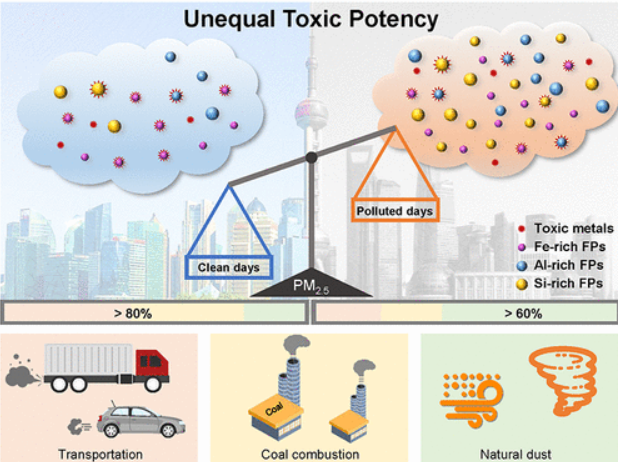

These MCFPs formed around 80% of all metal particles in the city’s air.

Key finding

Even when PM2.5 levels were within global safety limits (under 15 µg/m³) — i.e., on “clear days” —

→ air was still highly toxic to human lung cells.

Oxidative stress (chemical damage in cells) was 8.1× higher, and

Cell death was 6.3× higher compared to polluted days.

So, the air looked cleaner but was chemically more dangerous.

Why this happens

The main culprits were iron-rich MCFPs mixed with other metals like manganese and lead.

These particles cause strong oxidative reactions, creating free radicals that damage DNA.

They mainly come from vehicle emissions and coal burning.

On hazy days, large dust particles dilute their effect — but on clear days, the proportion of toxic metal particles increases.

Implications

PM2.5 mass alone is a poor indicator of air safety.

Air that seems clean can still carry microscopic toxic metal particles that stay in lungs and organs for years.

Scientists recommend:

Air quality monitoring should not just count PM2.5,

but should also identify specific toxic components, especially iron-rich MCFPs.

Focus should shift to controlling emissions from vehicles and coal combustion.