India–UK FTA: A Double-Edged Sword for Access to Medicines

Context

-

The India–UK Free Trade Agreement (FTA) includes provisions on Intellectual Property (IP) that may impact the availability, affordability, and production of generic medicines.

-

Concerns are being raised by experts, academics, and access-to-medicine advocates.

Key Concerns in the FTA

A. Tilt Towards Patent Holders

-

IP clauses favour transnational pharmaceutical corporations.

-

Undermines public interest safeguards enshrined in the Indian Patents Act.

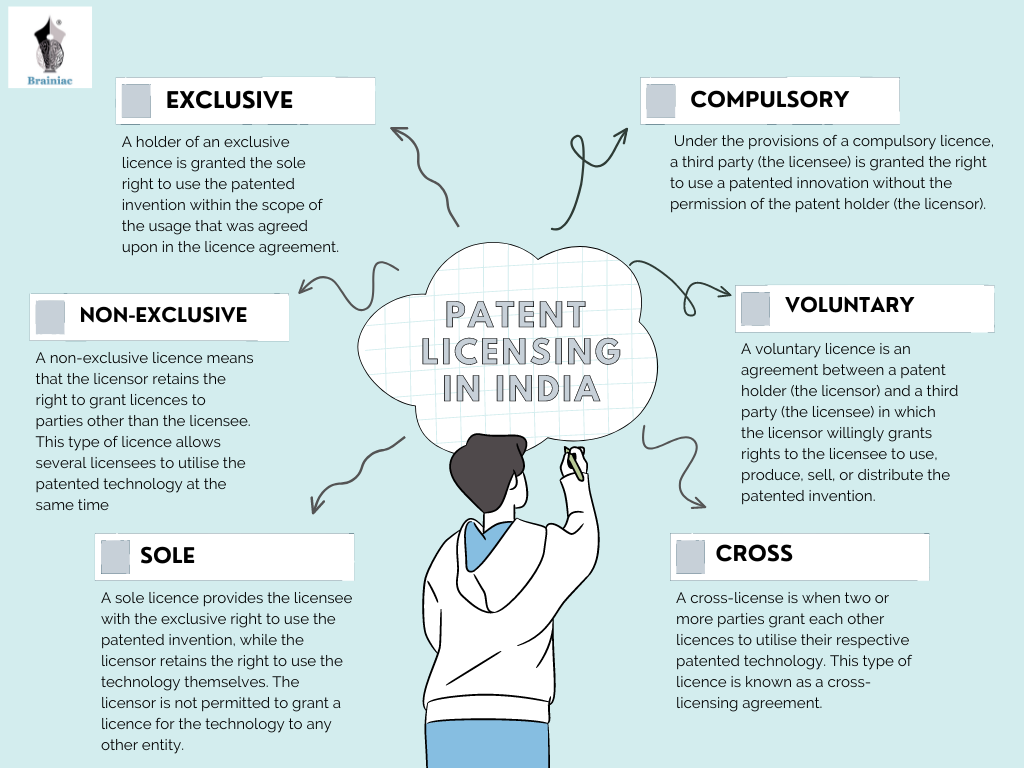

B. Voluntary Licensing vs Compulsory Licensing

-

Emphasis on voluntary licensing:

-

Relies on market forces, not state intervention.

-

Often comes with restrictive terms, royalty demands, and territorial limits.

-

Does not ensure substantial price reduction.

-

-

Reduces the government's power to issue Compulsory Licenses (CL), which were instrumental in past HIV/AIDS medicine access.

C. Dilution of Patent Working Requirements

-

Previously: Annual disclosure by patent holders on the working of the patent in India.

-

Now: Disclosure every 3 years.

-

Also, confidential information in reports will not be available publicly.

-

Implication: Harder to prove unmet needs—a ground for issuing CLs.

D. TRIPS-Plus Provisions

-

FTA includes TRIPS-Plus elements, such as:

-

Undermining Section 3(d) of Indian Patents Act (anti-evergreening clause).

-

Promoting harmonization of patentability standards.

-

Allows use of patent search/examination results from partner countries (may push for relaxed standards).

-

E. Evergreening Risk

-

Vague "best endeavour" clauses in IP chapter can dilute safeguards.

-

Could allow extension of patent life for minor modifications (e.g. new dosage forms) — blocking generics.

Supporters' Viewpoint

-

Trade proponents argue the FTA:

-

Gives zero-duty access for 99% of Indian pharma exports to UK.

-

UK pharma market set to grow from $45 bn (2024) to $73 bn (2033).

-

India's pharma exports to UK grew by 12.6% in FY24; generics alone at $910 million.

-

Reduced regulatory barriers = easier market entry + scope for India–UK healthcare collaboration.

-

Broader Implications

-

For India: Risks its global leadership in generic medicine production.

-

For Global South: Affordability of life-saving medicines in Africa, Latin America, Southeast Asia may be hit.

-

Contradicts India’s image as the ‘pharmacy of the developing world’.

Way Forward

-

Balance trade interests with public health safeguards.

-

Strengthen domestic pharma policies to:

-

Support MSMEs.

-

Ensure compulsory licensing remains robust.

-

-

Transparent monitoring of FTA implementation.

-

Protect Section 3(d) and public disclosure norms to ensure access to generics.

Voluntary Licensing

A voluntary license is a permission given by the patent holder (owner of the invention) to another party, allowing them to make, use, or sell the patented product or technology — with the patent holder’s consent and under agreed terms.

Key Features of Voluntary Licensing:

-

Mutual Agreement:

The patent holder voluntarily agrees to license their patent to another person or company — usually in exchange for royalties or a fee. -

Legal and Flexible:

It is a legal contract, and the terms (like duration, territory, royalty amount, etc.) are negotiated between the parties. -

Patent Owner Keeps Rights:

The original patent holder still owns the patent and can give licenses to multiple parties if they want. -

Used for Wider Access:

Voluntary licensing is often used in public health, such as allowing generic drug manufacturers to produce affordable versions of patented medicines, especially in developing countries.

Voluntary License vs. Compulsory License:

| Feature | Voluntary License | Compulsory License |

|---|---|---|

| Based on Consent? | Yes (by patent holder) | No (granted by government) |

| Usually with Royalties? | Yes | Yes, but often at lower rates |

| Common Use? | Pharma, tech, agriculture | Public health emergencies |